Link: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/cultural-stereotypes-multinational-banks

Graphic:

Excerpt:

Previous studies (e.g. Guiso et al. 2006, 2009) have used aggregate survey data from Eurobarometer to show that the volume of flows between pairs of countries is importantly affected by bilateral trust. A limitation of such country-level evidence is that average levels of trust are almost certainly correlated with unobserved characteristics of country pairs. To rule out confounding factors, we therefore develop a bank-specific measure of trust.

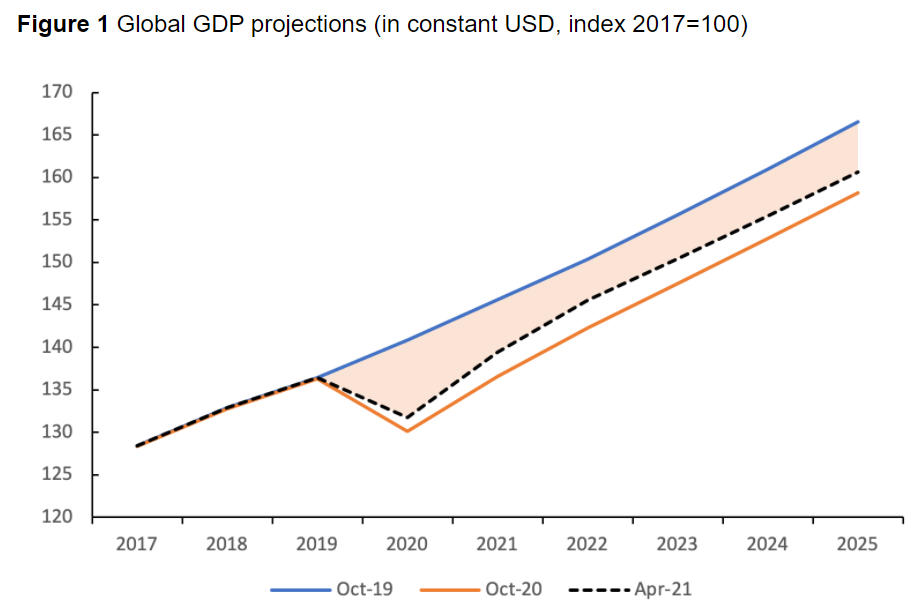

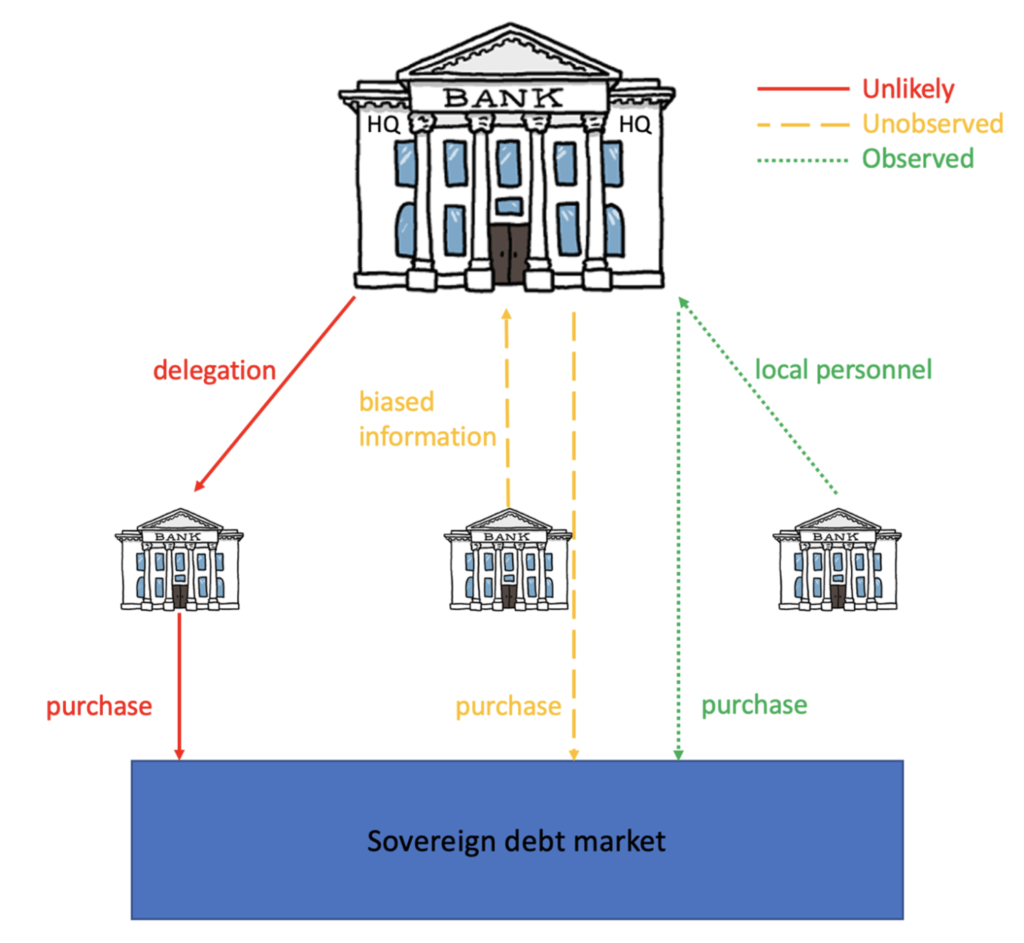

For this purpose, we model banks as hierarchies (as illustrated by Figure 1). Strategic decisions such as whether or not a bank should invest in a country are generally taken at bank headquarters. Portfolio managers working in the headquarters country or elsewhere are then responsible for implementing those decisions. Because we are concerned with investment decisions undertaken by headquarters, we focus our analysis on the extensive margin of sovereign exposures – whether or not a bank invests in the bonds of a country, as opposed to exactly how much it invests.

Given this framework, cultural stereotypes in subsidiaries can shape the soft information that subordinates transmit up the hierarchy to headquarters, where the broad parameters guiding portfolio investment decisions are set. They can affect how that soft information is received by directors, because the latter share the same stereotypes, reflecting the extent to which banks hire and promote internally across borders, such that the composition of bank boards and officers reflects the geography of the bank’s branch network. We provide empirical support for this framework by showing that multinational branch networks help predict the national composition of high-level managerial teams at bank headquarters.

Author(s): Orkun Saka, Barry Eichengreen

Publication Date: 23 Dec 2022

Publication Site: VoxEU