Link: https://reason.com/2023/10/04/the-debt-crisis-is-getting-real/

Excerpt:

When Yglesias wrote that column for Vox in 2016, the federal government owed about $19 trillion. Today, it owes more than $33 trillion, and we just added another $2 trillion in a fiscal year with no major national emergencies.

In short, the federal government followed Yglesias’ advice. But it might be more accurate to say it went along with what was clearly a bipartisan consensus formed in the mid-2010s: that borrowing was cheap, debt was easy to afford, and deficit spending allowed everyone to enjoy “a better life” with none of the downsides of austerity.

Unfortunately, the downsides have arrived.

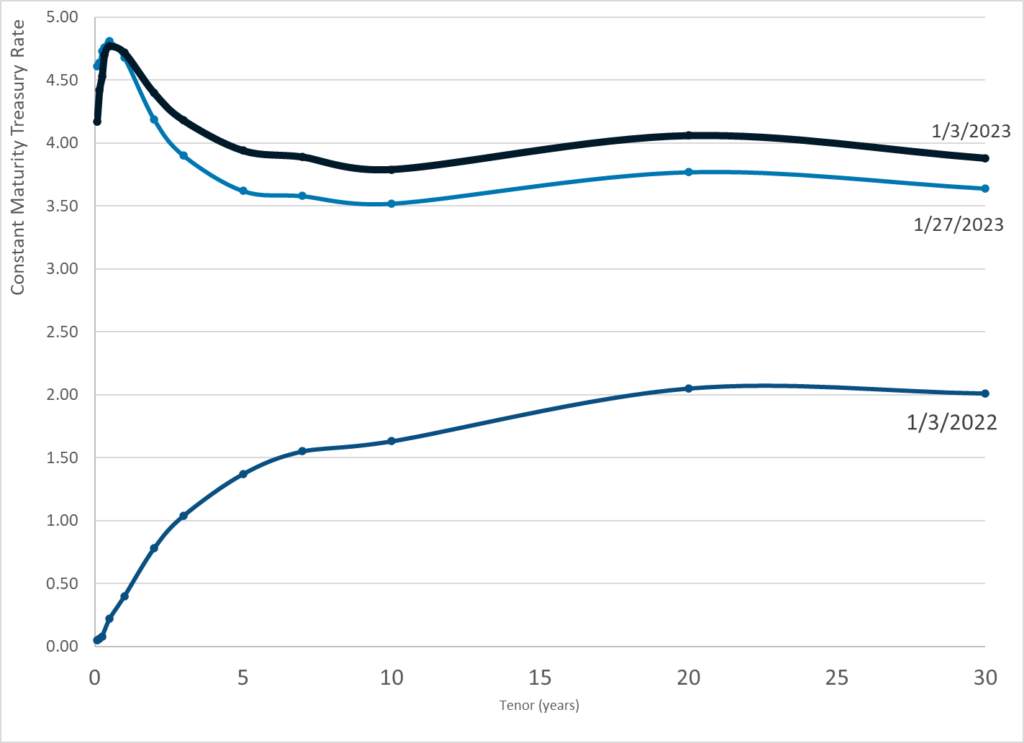

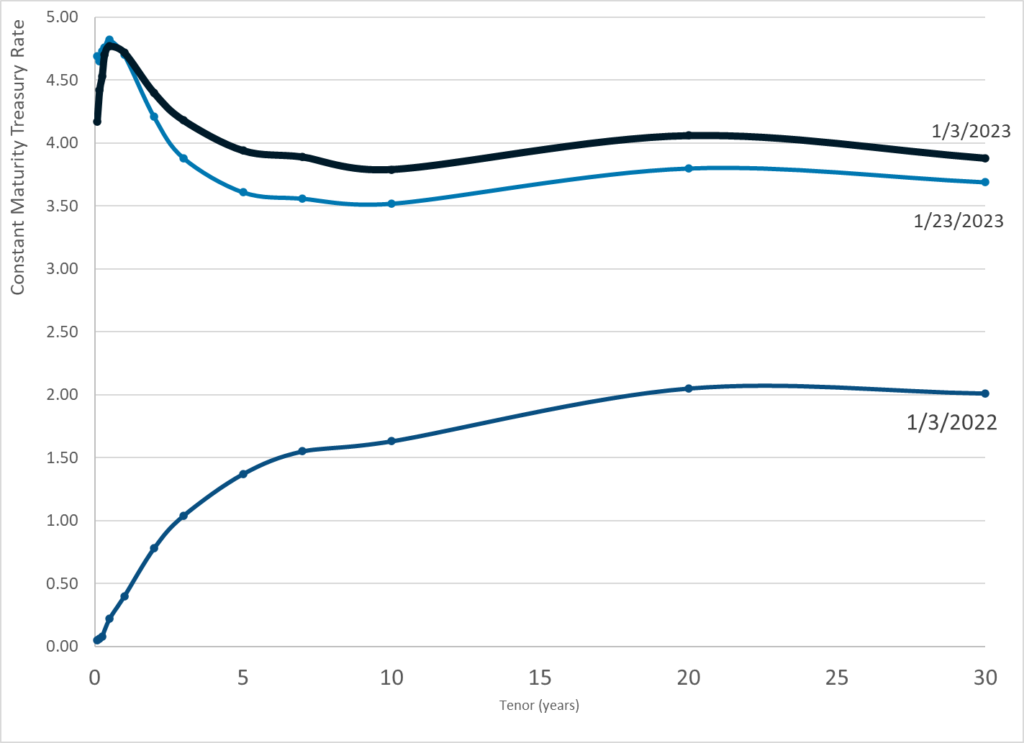

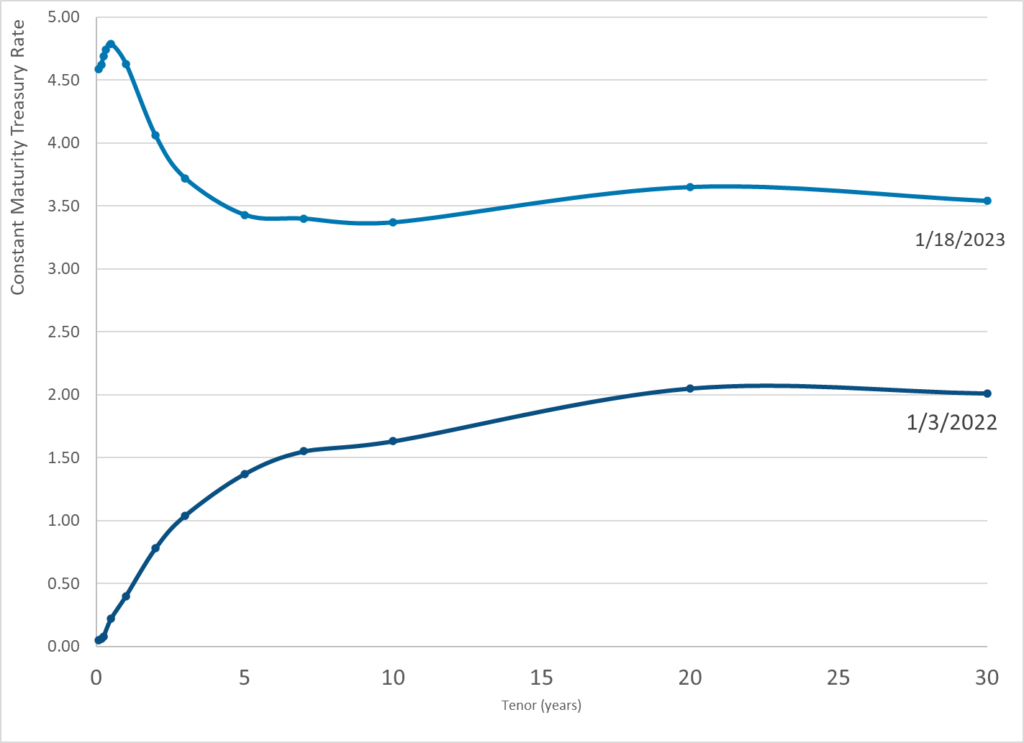

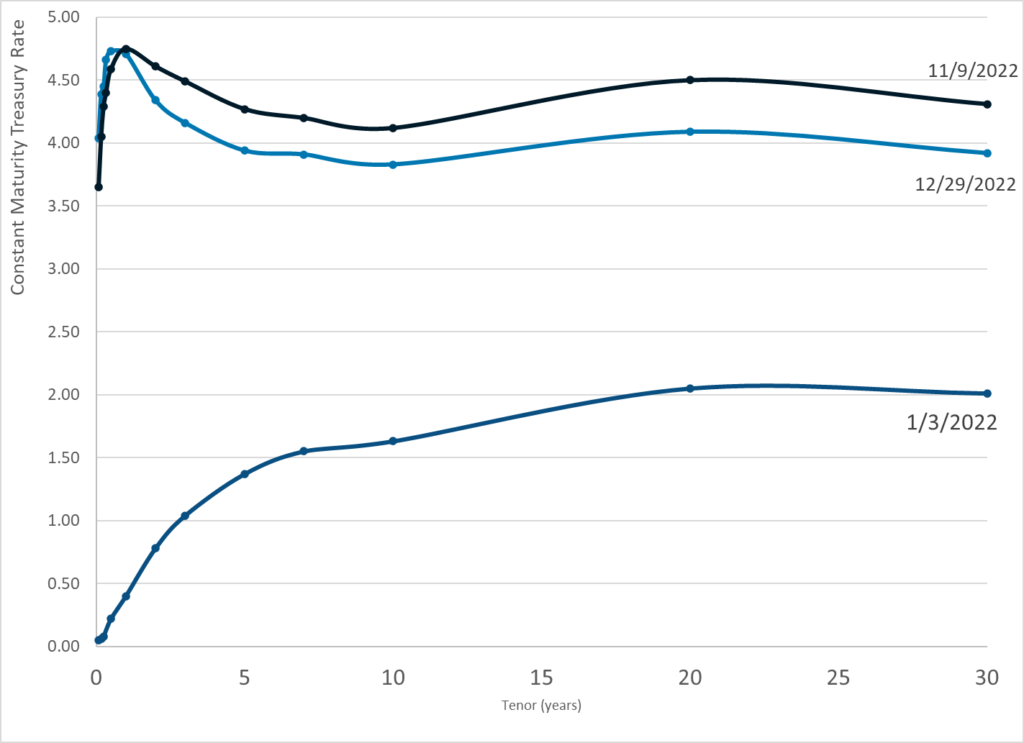

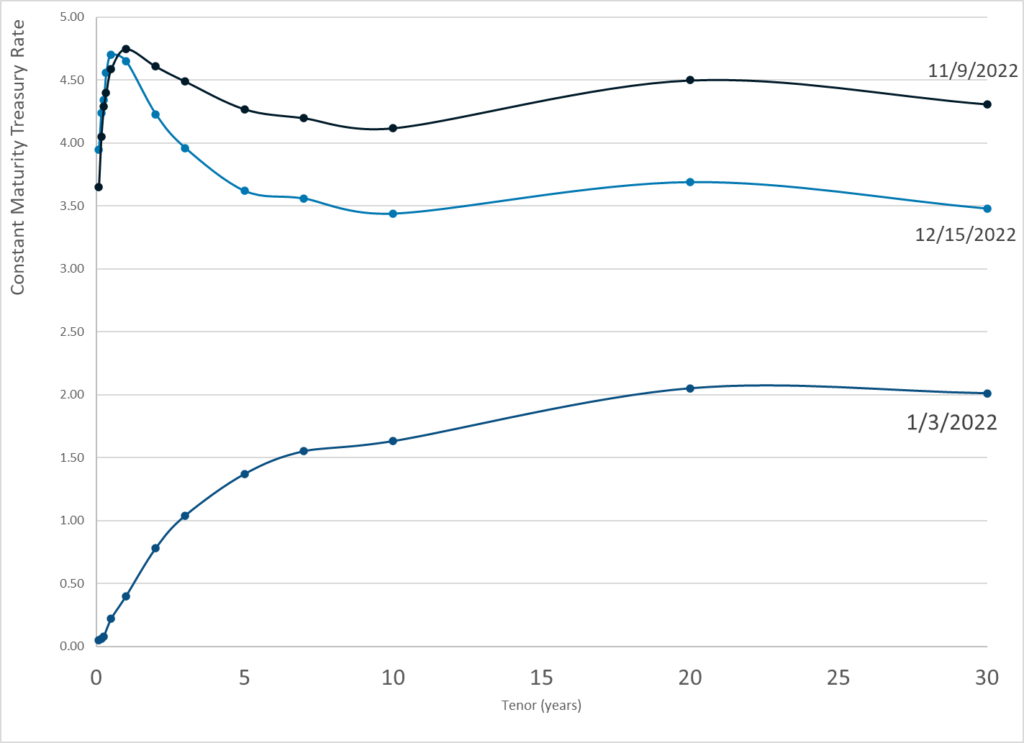

The yields on U.S. Treasury bonds are now hitting levels not seen in decades. The 10-year Treasury bond is nearing 5 percent, while the 20-year bond has already crossed that threshold—and some analysts expect higher yields to be coming, CNBC reported Tuesday.

Why does that matter? “We took out a mortgage thinking we’d be paying 2%, but now we’re paying 5%,” Marc Goldwein, director of policy at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) wrote on X (formerly known as Twitter) on Tuesday.

Unlike most mortgages, which have fixed interest rates, much of the U.S. government’s debt is tied up in short-term bonds which periodically “roll over” into new bonds with updated interest rates. As a result, higher interest rates mean higher interest payments—and those funds come directly out of the federal budget, leaving less revenue for everything else the government might aspire to do, whether funding welfare programs or buying more fighter jets.

“That debt, borrowed at low rates, is now being rolled over into Treasuries paying interest rates between 4.5 and 5.6 percent,” the CRFB explained last month. “Though borrowing seemed cheap during those periods, policymakers failed to account for rollover risk, and we are now facing the cost.”

Interest payments on the debt will be the fastest-growing part of the federal budget over the next three decades, according to the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) projections. In the shorter term, interest payments are set to triple by 2033, when they will cost an estimated $1.4 trillion—a total that will only grow higher if more unplanned borrowing takes place before then, or if interest rates rise higher than the CBO expects.

Author(s): Eric Boehm

Publication Date: 4 Oct 2023

Publication Site: Reason