Graphic:

Excerpt:

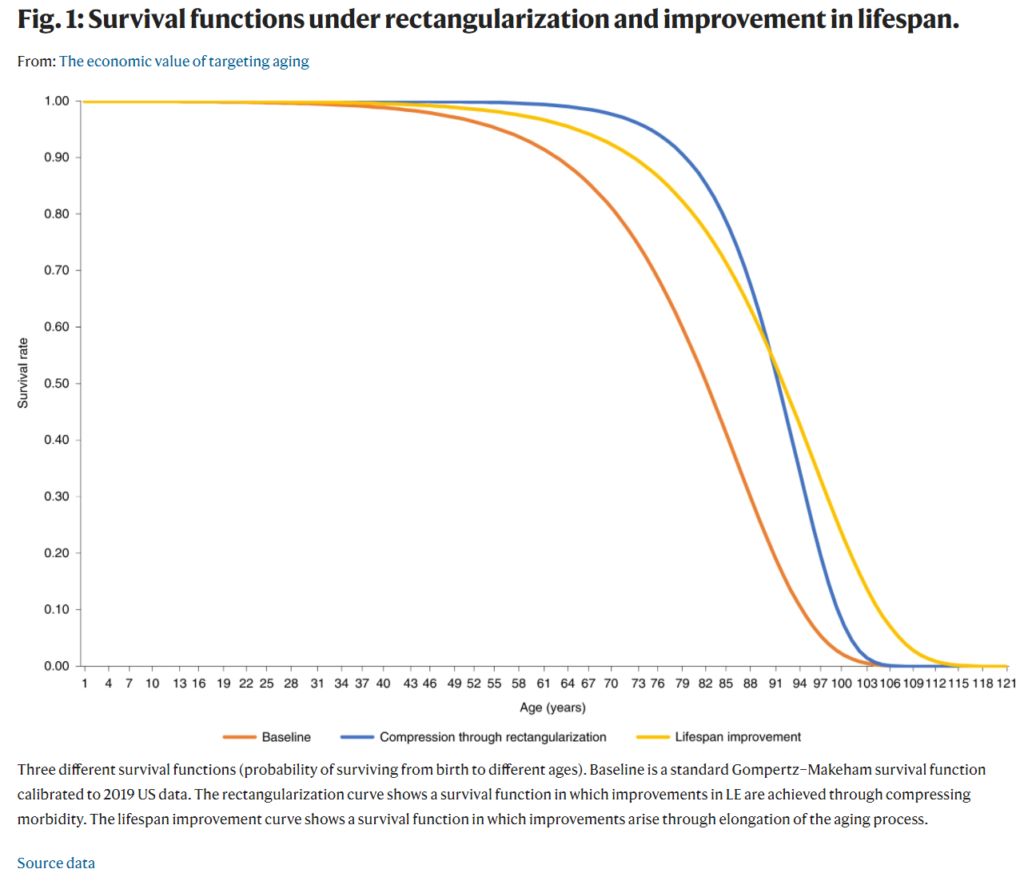

Developments in life expectancy and the growing emphasis on biological and ‘healthy’ aging raise a number of important questions for health scientists and economists alike. Is it preferable to make lives healthier by compressing morbidity, or longer by extending life? What are the gains from targeting aging itself compared to efforts to eradicate specific diseases? Here we analyze existing data to evaluate the economic value of increases in life expectancy, improvements in health and treatments that target aging. We show that a compression of morbidity that improves health is more valuable than further increases in life expectancy, and that targeting aging offers potentially larger economic gains than eradicating individual diseases. We show that a slowdown in aging that increases life expectancy by 1 year is worth US$38 trillion, and by 10 years, US$367 trillion. Ultimately, the more progress that is made in improving how we age, the greater the value of further improvements.

Author(s): Andrew J. Scott, Martin Ellison, David A. Sinclair

Publication Date: 5 July 2021

Publication Site: Nature Aging