Link:https://www.actuary.org/node/14837

Graphic:

Excerpt:

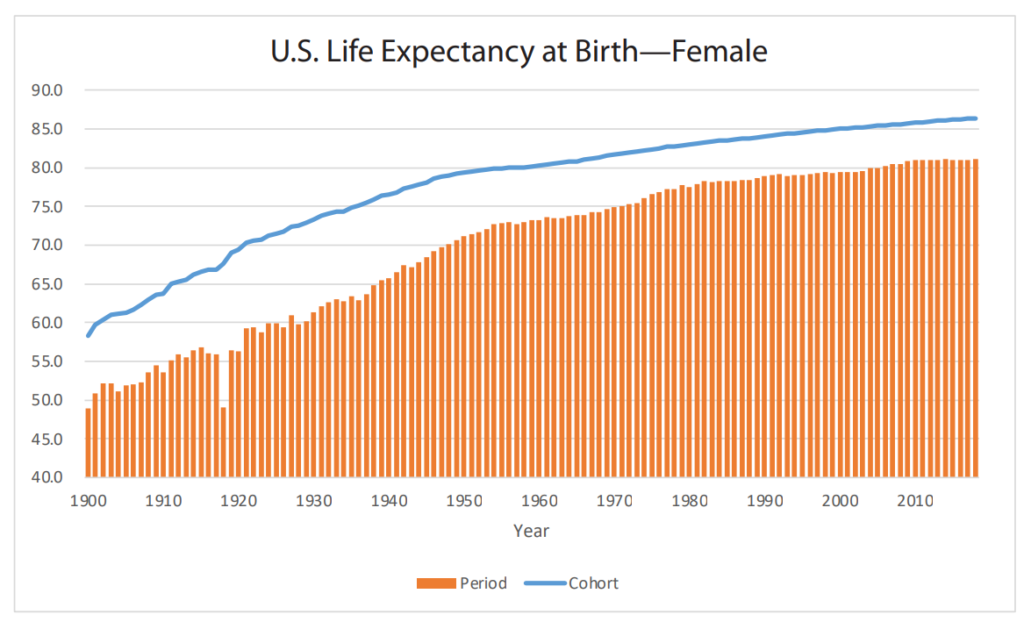

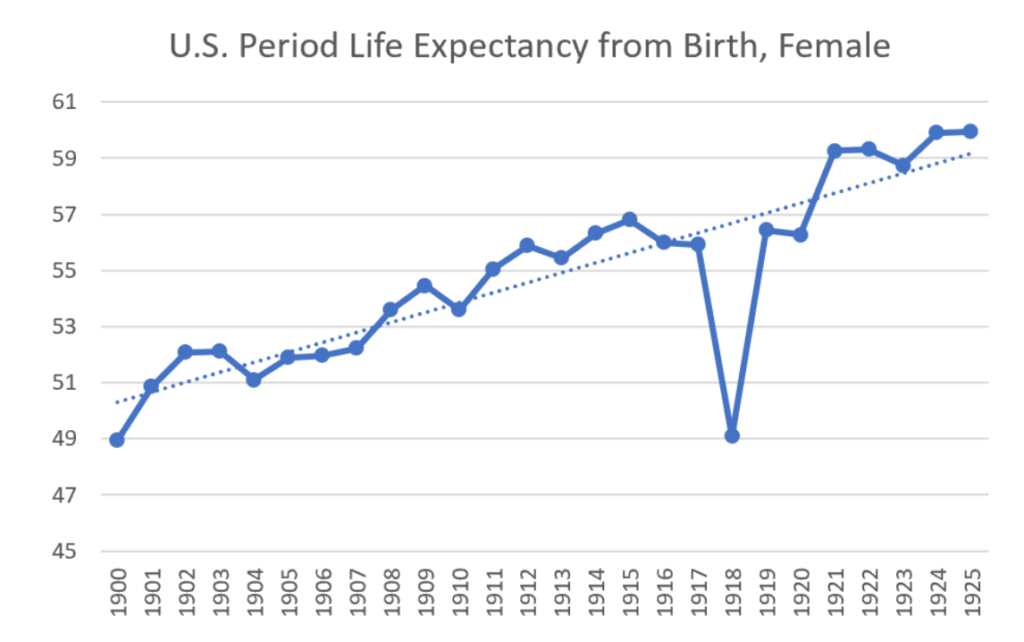

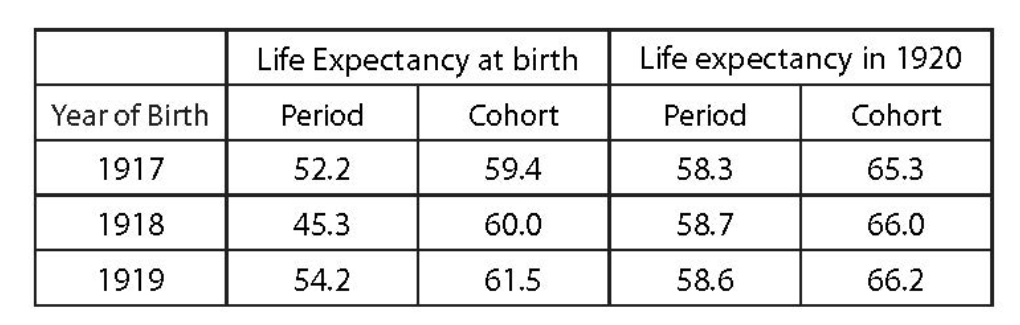

Period life expectancy measures demonstrate fluctuations that reflect events that influenced mortality in this particular period.14 For example, the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 resulted in a dramatic decrease in period life expectancy, which was more than offset by an increase in period life expectancy the next year. A male baby born in 1917 had a period life expectancy of 52.2 years, while a male baby born in 1918 had a period life expectancy of only 45.3 years—a reduction of almost 7 years.15 The following year, a male newborn had a period life expectancy of 54.2, an increase of almost 9 years over the period life expectancy calculated in 1918 for a newborn male. These changes are much larger than those seen thus far with COVID-19, demonstrating the relative severity of that earlier pandemic relative to the current one.

It is instructive to review the impact of calculating life expectancies on a cohort basis, rather than a period basis, for these three cohorts of male newborns in the late 1910s. Using mortality rates published by the SSA for years after 1917, for a cohort of 1917 male newborns, the average life span was 59.4; for the 1918 cohort, average life span was 60.0; and for 1919, it was 61.5. Even these differences are heavily influenced by the fact that the 1917 and 1918 cohorts had to survive the high rates of death during 1918, while the 1919 cohort did not.

If both period and cohort life expectancy are measured as of 1920 for each of these groups (the 3-year-old children who were born in 1917, 2-year-old children who were born in 1918 and 1-year-old children who were born in 1919), differences are observed in these measures as they narrow substantially because the high rates of mortality during 1918 have no effect on those who survived to 1920. This is summarized in the table below.

Author(s): Pension Committee

Publication Date: December 2021

Publication Site: American Academy of Actuaries