Graphic:

Excerpt:

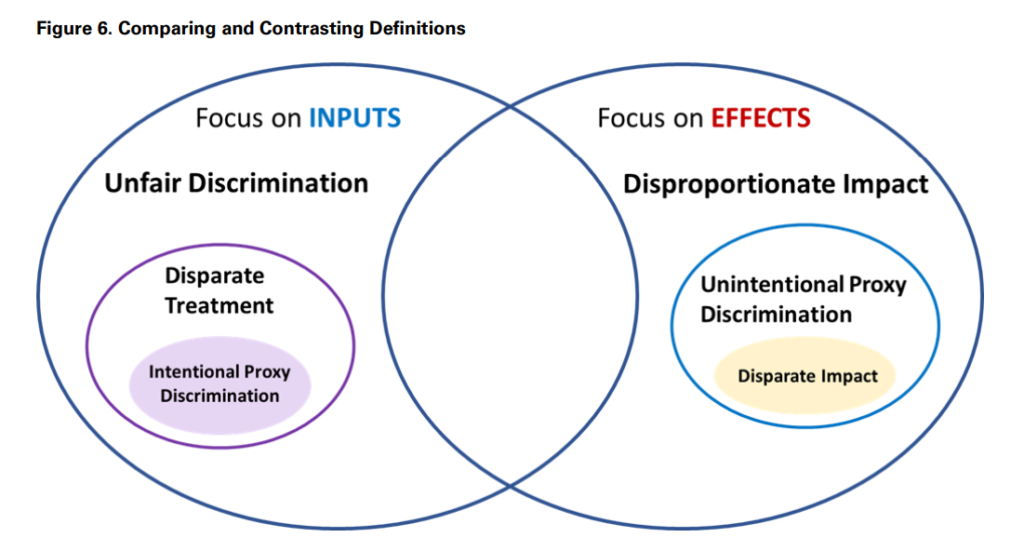

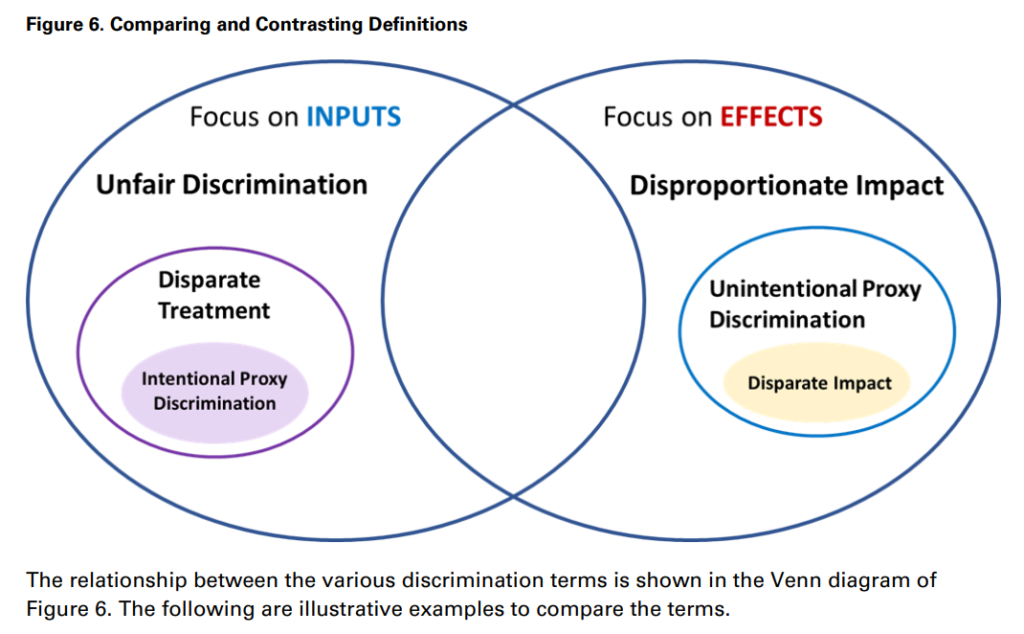

Unfair Discrimination without Disproportionate Impact. As previously defined, unfair discrimination occurs when rating variables that have no relationship to expected loss are used. A hypothetical example could be if an insurer decided to use rating factors that charged those with red cars higher rates, even if the data did not show this. In this case, there would be no disproportionate impact, assuming protected classes do not own a large majority of red cars.

Disparate Treatment. Disparate treatment and unfair discrimination are not directly related if we use the Fair Trade Act definition of unfair discrimination. However, in states where rating on protected class is defined to be unfair discrimination, disparate treatment would be a subset of unfair discrimination. In such cases, an insurer would explicitly use protected class to charge higher rates, with the intention of prejudicing against that class.

Intentional Proxy Discrimination. If proxy discrimination is defined to require intent, it would be a subset of disparate treatment, whereby an insurer would deliberately substitute a facially neutral variable for protected class for the purpose of discrimination. Redlining is an example of this type of discrimination, given the use of location characteristics as proxies for race and social class.

Disproportionate Impact. Disproportionate impact focuses on effect on protected class, even if there is a relationship to expected loss. An example of this is the one mentioned in the AAA study, whereby a rating plan that uses age could disproportionately impact a minority group if those in that minority group tend to have higher risk ages. This disproportionate impact is not necessarily the same as proxy discrimination, since it is likely that even after controlling for minority status, age would have a relationship to

expected costs.Unintentional Proxy Discrimination. If proxy discrimination is defined to be unintentional, the focus is more on disproportionate outcomes and the variables used to substitute for protected class. Several variables are being investigated by regulators to potentially be proxy discrimination and include criminal history for auto insurance rating. In order to prove proxy discrimination, an analysis would have to be performed to understand the extent to which criminal history proxies for minority status, and whether its predictive power would decrease when controlling for protected class. It is important to note once

again that terms like “unintentional proxy discrimination” may be subsumed by “disparate impact,” but they are included in this paper to show how various stakeholders use the term differently.

Disparate Impact. Disparate impact is unintentional discrimination, where there is disproportionate impact, but also other legal requirements, such as the existence of alternatives. To date, no disparate impact lawsuits against insurance companies have been won. An example of potential disparate impact (although it was not litigated as a lawsuit) is from health care. Optum used an algorithm to identify and allocate additional care to patients with complex healthcare needs. The algorithm was designed to create a risk score for each patient during the enrollment period. Patients above the 97th percentile were automatically enrolled in the program and thus allocated additional care. Upon an independent peer review of the model, researchers found that the model was in fact allocating artificially lower scores to Black patients, even though the model did not use race. The reason behind this was the model’s use of prior healthcare costs as an input. Black patients typically spend less than white patients on health care, which artificially allocated better health to Black patients.18

Unfair Discrimination and Disproportionate Impact. In this case, an insurer would use a variable that both has no relationship to expected loss, but also has an outsized effect on protected classes. An example of this could be the same red car case above, but where protected classes also owned almost all the red cars. In this case, higher rates would create a disproportionate effect on protected classes, while also having no relationship to expected loss.

Author(s): Kudakwashe F. Chibanda, FCAS

Publication Date: 2022

Publication Site: Casualty Actuarial Society