Graphic:

Excerpt:

Life technical risks measure the possible losses from deviations from the best estimate assumptions relating to life expectancy, policyholder behavior, and expenses. The life technical risks are captured through mortality, longevity, morbidity, and other risks. The methodology for calculating the capital adequacy for these four risk categories remains unchanged under the proposed method, apart from the recalibration of capital charges or the consolidation of defining categories within each risk. Comparing to the current GAAP based model, charges have materially increased across all categories partly due to higher confidence intervals, with notable exceptions of longevity risk, with reduced charges across all stress levels (changes applicable to U.S. life insurers are illustrated in Tables A2 to A5 in the Appendix linked at the end of this article). Please note that S&P’s current capital model under U.S. statutory basis does not have an explicit longevity risk charge. However, this article focuses on comparison to current GAAP capital model[1] that is closer to the new capital methodology framework.

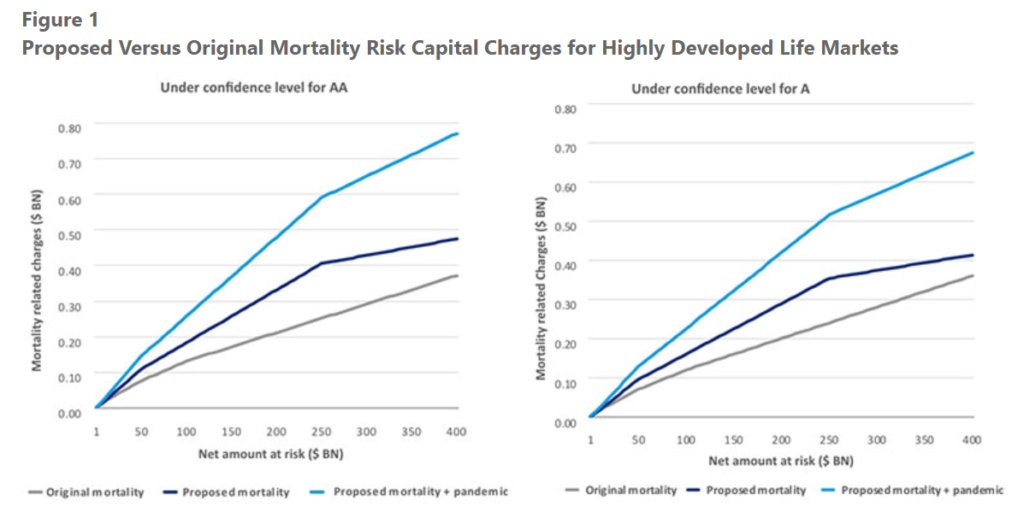

For mortality risk, lower rates are charged for smaller exposures (net amount at risk (NAR) $5 billion or less) with the consolidation of size categories, but higher rates are charged for NAR between $5 billion and $250 billion, with an average increase of 49 percent for businesses under $400 billion NAR. A new pandemic risk charge (Table A3 in the Appendix linked at the end of this article) will further increase mortality related risk charges to be 109 percent higher than original mortality charges under confidence level for company rating of AA, and 93 percent higher for confidence level for company rating of A, respectively, on average (Figure 1). The disability risk charge rates increased moderately for most products, across all eight product types such that the increase of disability premium risk charges is 6 percent under confidence level for AA, and 2 percent for A, respectively. In addition, the proposed model introduced a new charge on disability claims reserve, ranging from 13.7 percent of total disability claims reserves for AAA, to 9.6 percent for BBB. However, the proposed model provides lower capital charge rates in longevity risk and lapse risk.

Author(s): Yiru (Eve) Sun, John Choi, and Seong-Weon Park

Publication Date: September 2022

Publication Site: Financial Reporting newsletter of the SOA