Link:https://www.governing.com/finance/public-pensions-double-check-those-shadow-banker-investments

Excerpt:

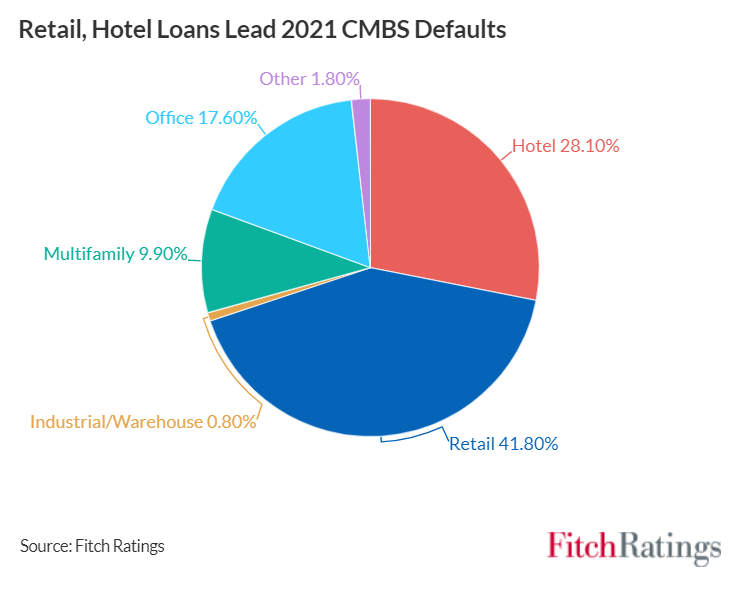

For almost a decade leading up to 2021, bond yields were suppressed by low inflation and central bank stimulus. To make up for scanty interest rates on their bond investments, many public pension funds followed the lead of their consultants and shifted some of their portfolios into private credit funds. These “shadow bankers” have taken market share from traditional lenders, seeking higher interest rates by lending to non-prime borrowers.

Even during the pandemic, this strategy worked pretty well, but now skeptics are warning that a tipping point may be coming if double-digit borrowing costs trigger defaults. It’s time for pension trustees and staff to double-check what’s under the hood.

For the most part, the worst that many will find is some headline risk with private lending funds that underwrite the riskiest loans in this industry. Even for the weakest of those, however, the problem will not likely be as severe as the underwater mortgages that got sliced, diced and rolled up into worthless paper going into the global financial crisis of 2008. And until and unless the economy actually enters a full-blown recession, many of the underwater players will still have time to work out their positions.

The point here is not to sound a false alarm or besmirch the private credit industry. Rather, it’s highlighting what could eventually become soft spots in some pension portfolios in time to avoid doubling down into higher risks and to encourage pre-emptive staff work to demonstrate and document vigilant portfolio oversight.

Author(s):Girard Miller

Publication Date: 8 Aug 2023

Publication Site: Governing