Link: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2763826

Graphic:

Abstract:

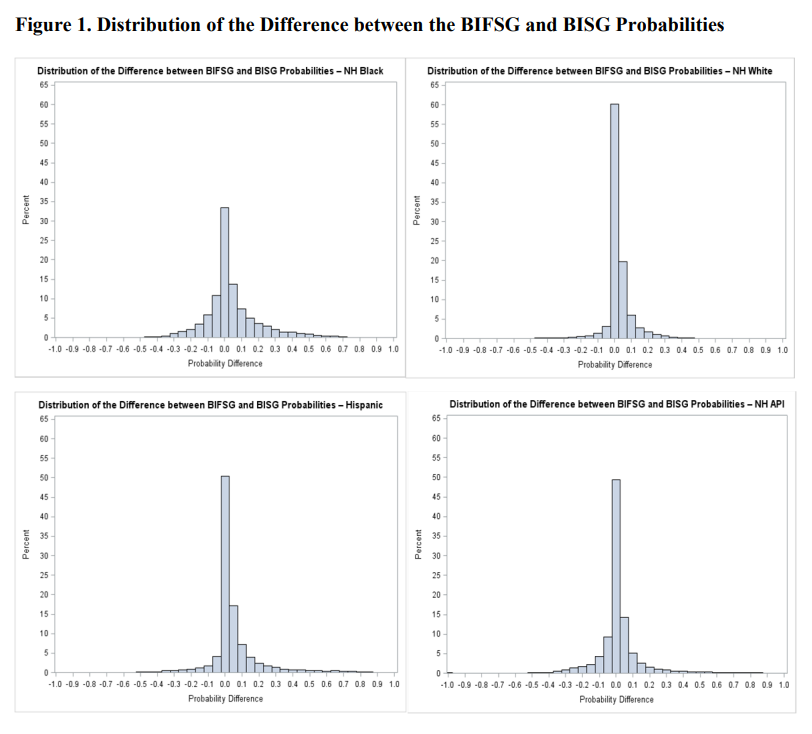

This paper uses a recent first name list to improve on a previous Bayesian classifier, the Bayesian Improved Surname Geocoding (BISG) method, which combines surname and geography information to impute missing race and ethnicity. The proposed approach is validated using a large mortgage lending dataset for whom race and ethnicity are reported. The new approach results in improvements in accuracy and in coverage over BISG for all major ethno-racial categories. The largest improvements occur for non-Hispanic Blacks, a group for which the BISG performance is weakest. Additionally, when estimating disparities in mortgage pricing and underwriting among ethno-racial groups with regression models, the disparity estimates based on either BIFSG or BISG proxies are remarkably close to those based on actual race and ethnicity. Following evaluation, I demonstrate the application of BIFSG to the imputation of missing race and ethnicity in the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, and in the process, offer novel evidence that race and ethnicity are somewhat correlated with the incidence of missing race/ethnicity information.

Author(s):

Ioan Voicu

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)

Publication Date: February 22, 2016

Publication Site: SSRN

Suggested Citation:

Voicu, Ioan, Using First Name Information to Improve Race and Ethnicity Classification (February 22, 2016). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2763826 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2763826