For example, Oakland, Calif., cleverly figured out in 1985 that it could issue tax-exempt bonds to fund its underwater pension plan, the proceeds of which it in turn would invest in normal pension portfolio holdings like taxable stocks and corporate bonds with a higher long-term return. It was a strategy almost certain to make a profit over time, even with the ups and downs in the stock market, but it didn’t take long for the IRS to put an end to that ploy as an abuse of the tax exemption. Thereafter, the IRS ruled, such pension bonds must be taxable.

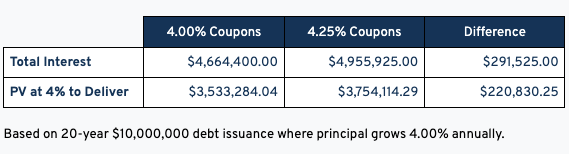

Likewise, the arbitrage police have played cops-and-robbers with clever public financiers who invest their cash during construction periods at interest rates higher than their tax-exempt cost of money. Using today’s interest rate levels, for example, a tax-exempt 20-year AAA-rated bond can be issued with coupons around three-and-a-half percent and the proceeds reinvested in Treasury bills and notes at 4 to 5 percent. In almost any year like this one, there’s a profit to be gleaned when borrowing tax-exempt and reinvesting at taxable rates.

….

There is also a new controversy brewing in a niche sector of the muni bond market, in which issuers of taxable bonds are finding an opportunity to refinance at lower tax-exempt rates. Investors are suing them. It’s premature to guess how this issue will be resolved in the courts, but worth watching.

….

As interest rates drift lower in tandem with hoped-for disinflation, muni bond professionals are starting to chat up the idea that soon we’ll see a wave of advance refundings, in which a municipality can refinance its debt at a lower interest rate. In corporate America, the finance team must usually wait until the issue’s maturity or call date before refinancing. In muni-land, however, there is a unique situation that is peculiar to the tax-exempt world: the opportunity to issue new bonds to replace the old ones at a lower interest rate before their scheduled call date — typically within 10 years after issuance — by setting up an escrow fund to pay off the original debt when it is callable.

It doesn’t take a math or market genius to figure out that this advance refunding strategy is susceptible to abuses. In theory and previously in practice, it could be repeated several times over the life of the original bonds: wash, rinse and repeat. So the IRS caught on to this and Congress put a limit — of one — on such deals. To accommodate this unique feature of the muni market, the Treasury Department even created a special class of its own securities, known as the State and Local Government Series (SLGS, or “slugs” in industry jargon), which bear interest rates equal to the new borrowing rate to preclude the arbitrage profit gambit.

The political challenge for municipal officials today is that underwriters and advisers are keen to promote these advance refundings as soon as they become feasible. Some will compete with each other to make the first pitch to win an engagement even if it’s not optimal longer term. The motto of some hucksters is “whoever gets to the decision-makers first, wins.” All they really want is the engagement fees; to them, a dollar earned today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow, so they get lathered up without necessarily showing their clients the potential to save even more if they wait a couple years for even lower rates. This year and next could be just such a time period, depending on when you think the next national recession will occur.

Mostly it will be the muni bonds sold in 2022 and early 2023, when interest rates were peaking (above 4 percent on AAA paper and maybe 5 percent for lower ratings), that the advance-refunding promoters will pitch. Just remember that the IRS rules now prohibit multiple advance refundings: It’s one bite of the apple, and there will be an opportunity cost for jumping the gun ahead of lower long-term interest rates in future years. Although short-term interest rates are expected to decline, it’s not so obvious that the longer end of the Treasury and muni bond yield curves will follow in this business cycle, at least until the next recession. Refundings are almost always timely in recessions, but can be premature in the middle of an interest rate cycle.